Crush injury

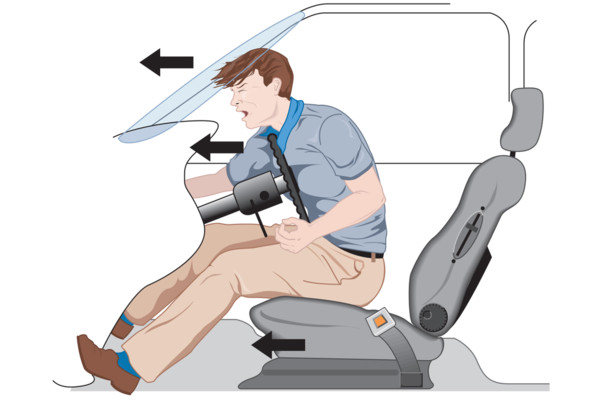

A crush injury occurs when a body part is subjected to a high degree of pressure after being squeezed between two heavy or immobile objects. Damage caused by a crush injury can include: laceration, fracture, bleeding, and bruising and/or crush injury syndrome.

Sign and symptoms

Sign and symptoms

- Pain at the site

- Tenderness

- Deformity

- Associated wound and blood loss

Care and treatment

- Call Triple Zero (000) for an ambulance

- Reassure casualty

- Treat any wounds

- Treat any fractures

First aid requires careful assessment. If the area has been compressed for a long time it may be best to wait for emergency services to arrive, or seek advice when you call Triple zero (000), before removing the crushing weight, as a special trauma suit or intravenous fluids may be needed before the weight is released

Crush injury syndrome

A compressing force which traps a casualty can cause crush injury syndrome. This force, if applied to a large muscle mass, e.g. the thigh, causes the body to produce large quantities of acid and complex electrolytes, especially potassium, around the affected muscles. On release of the compressing force, the liberated blood takes the concentrated chemicals to the heart with often fatal results. In addition, there is often a sudden loss of blood on releasing the compressing force.

Crush injury syndrome does not occur every time a casualty is trapped, but the first aid provider should consider the risk. As a general rule, the requirement for consideration is based on three criteria:

- A large muscle mass is involved

- Prolonged compression

- Compromised blood circulation

For instance, entrapment of a hand is unlikely to initiate the syndrome (no major muscle mass). The major problem that faces the first aid provider when dealing with suspected crush injury is dissuading helpful bystanders from attempting to remove the compressing force without assessing the situation first. Extended compression time

Sign and symptoms

- Large muscle mass involved

- Absent pulse and capillary return in the lower part of the limb

- Weak, rapid pulse

- Pale, cool, clammy skin

- Usually absence of pain in the affected region

- Onset of shock

Care and treatment

- Call Triple Zero (000) for an ambulance

- Relieve the crushing force as quickly and gently as possible, provided it is safe

- to do so

- Reassure casualty

- Treat any other injuries

- Be prepared to assist the medical support team

Manual handling

Back injuries cost the Australian taxpayer and commercial and industrial interests, many millions of dollars annually. Initial medical costs and the cost of prolonged rehabilitation of back injury patients account for the major proportion of industrial insurance payouts. As well as being an expensive injury, an injured back is painful and debilitating. In most cases, the injury was preventable.

The spinal column is not designed to withstand abnormal flexion under load. Lifting weights and carrying loads are normal functions for active humans; however, care must be taken not to exceed the ability of the spine to adequately support this physical activity. When this ability is exceeded, the resultant failure of the spine causes acute and chronic pain and a reduced capacity to function normally.

It is in everybody's interest, whether employer, employee or individual, to avoid back injuries by simply 'thinking before lifting'. Factors associated with back injury

Occupational

Constant manual handling, frequent bending and flexing of the spine, a poor ergonomic workplace and repetitive back movements, all provide a basis for acute injury or chronic complaint.

Personal

Individual strength, age, posture and degree of fitness are important factors.

Medical/Historical

Previous back complaints, evidence of scoliosis or similar medical conditions and previous education in back care procedures, will generally, in conjunction with personal factors, dictate the degree of abuse the back can absorb. The ultimate aim in avoiding back injury is to identify and eliminate potential risks before any injury is sustained.

- To do this effectively, individuals should identify, assess and control any risk factors.

- Identify risk factors by reviewing past procedures and comparing the injury rates.

- Observe and analyse any existing or potential problems. Consider any personal medical or physical limitations. Consult other individuals or organisations.

Assess the risks involved:

- Is manual handling essential?

- What options are available?

- Is the right person involved?

Control any risk by reducing the necessity for manual handling by using alternative means of handling, by maintaining a SAFE work or home environment (no slippery floors or obstructions) and especially by educating all those involved in safe lifting techniques.

When lifting or moving a load, consider not only the weight of the object, but its size and shape, the distance it is to be carried, the height it will have to be lifted and its position prior to lifting. In fact, does it need lifting or will it be better to push or pull the load?

Lifting or moving a load

- Consider the load, - size, shape, etc.

- Consider need for mechanical or manual assistance

- Position legs apart - one foot level with the load

- Keep back straight, look up

- Bend from the hips, avoid 'twisting' the body

- Tighten the stomach muscles, but don't hold breath

- BEND THE KNEES

- Lift with the legs, not the back

- Keep the load close to the body

- Keep carrying distance short

- Avoid changing grip or 'jerking' the load Deposit the load by bending the knees and

- Keep the back straight (reverse order of lifting)

- If pulling or pushing, let the legs do the work

Pregnant women should take special care when lifting, as their spine adjusts to cater for the physical changes of the body. A pregnant woman's ligaments are also affected by hormonal changes and 'soften' considerably. Any heavily pregnant woman who lifts or carries a heavy, restless, wriggling child is at risk of back injury or worse.